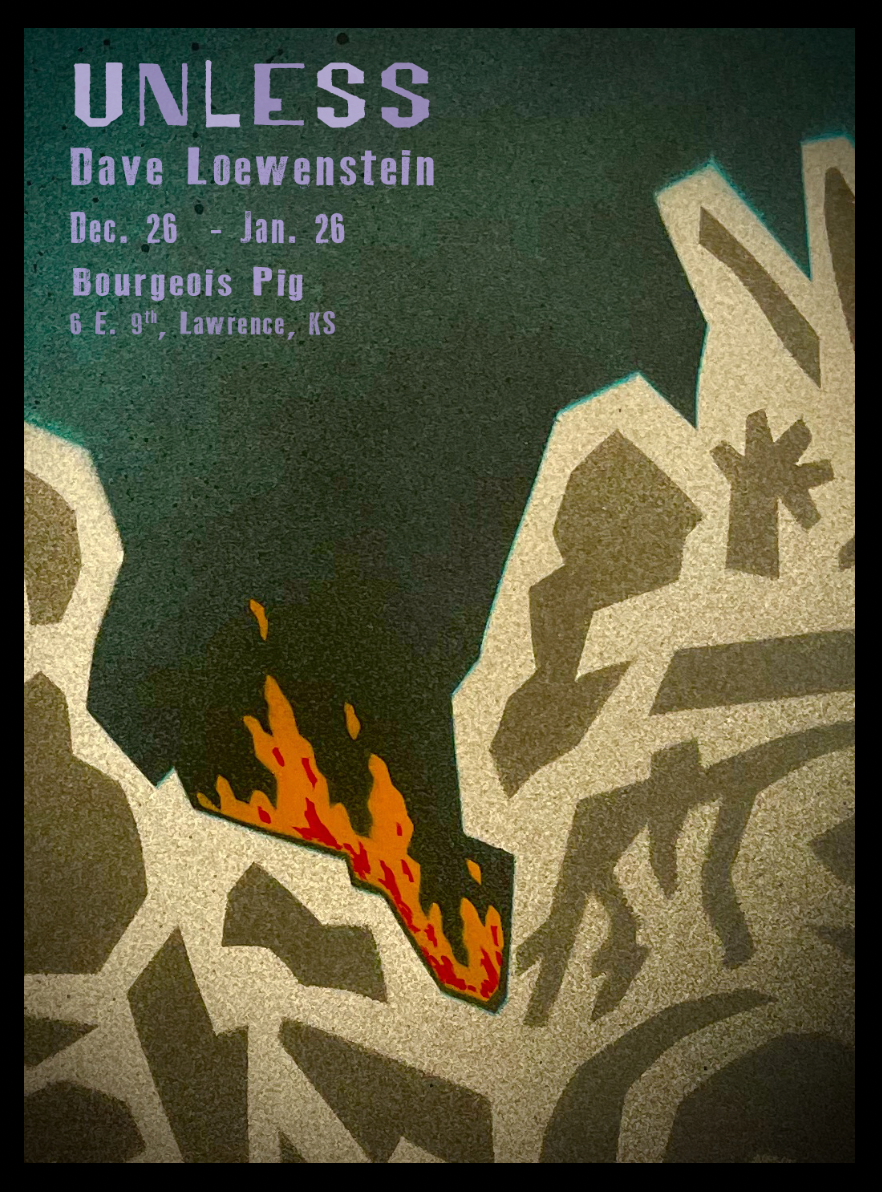

The Erratics

This series of prints began with a small mystery. I wondered how the large pink stone (over three-hundred pounds) that sat between the alley and garage door of my studio got to where it was. It didn’t appear to serve a function in relation to the building or have a decorative purpose, but it was too big to not have been placed there intentionally, I thought. For more than twenty years I’d speculated, usually when I had to get around it to take out the garbage or when rain turned its surface into a deep maroon, flecked with a constellation of white crystals like a giant gumdrop, who would have put it there.

The answer didn’t occur to me until I began working with Pauline Sharp on what we called, at the time, the “Between the Rock and Hard Place” project, and that was that the stone had not been placed there by people but by nature. The Sacred Red Rock ( Iⁿ‘zhúje‘waxóbe ) that we were working to bring attention to and the boulder in front of my studio were both red quartzite glacial erratics, survivors of earth’s early years that had hitched a ride on a glacier during the last ice age from what we now call South Dakota and ended up in Kansas.

What for me had been a simple rock and sometimes nuisance became a direct connection to primordial forces, embodied with characteristics of strength, beauty and perseverance. Learning this expanded the story I had about the place where I lived, in the same way that learning the location of the North Star in the night sky had changed the way I thought about outer space when I was a kid. After solving the mystery, I began to see these stones in places I hadn’t before, as if they’d been hidden or camouflaged by my simple lack of regard.

More conspicuous than concealed, I’d find them serving as bases for monuments in town squares and city parks. There were monuments to The Settlers, the Pony Express, the Oregon Trail, to the military, to philanthropists and even a monument to the glacier itself in Blue Rapids. But the one that inspired this series had an added feature that showed how people-built landscapes can create unintended juxtapositions that reveal truths otherwise obscured by the language of committee approved bronze plaques.

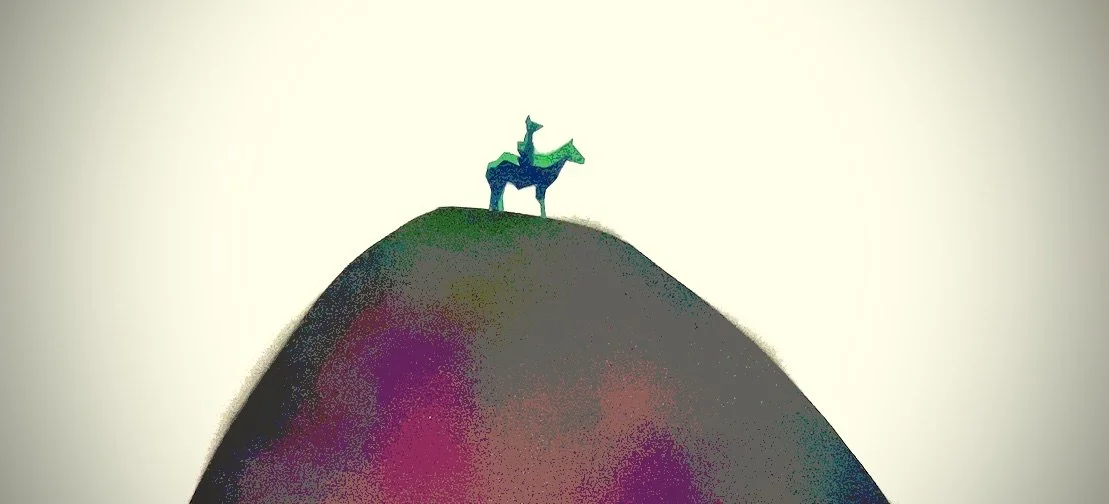

It was a dome shaped glacial erratic in Kansas City’s Penn Valley Park, embedded in the ground and rising up about four feet with a small bronze plaque on its face honoring the writer of the book, “The Annals of the City of Kansas and the Great Western Plains,” published in 1856. It’s an unremarkable monument, out of place and without context in the way many attempts at memorialization can gradually lose their relevance as time passes. But then I noticed, as I kneeled down to take a photo, that if you look at this stone from a certain angle, the iconic Kansas City statue known as “The Scout” appears to be standing in miniature right on top of it.

“The Scout” like the glacial erratic stone it appeared to be standing on were both originally from somewhere else – the stone from up north, and the subject of the statue, a Sioux scout, from their Tribe and Land. Seeing them together as unintended immigrants, removed from their homes by nature on one hand and by human interference on the other, inspired the first print in this series. The others, which all depict actual stones in northeast Kansas, were similarly influenced by the admiration (sometimes misplaced) that humans seem to have for these ancients and how we have tried to weave their majesty into our own stories.

The Long Goodbye

(adapted from the eulogy I gave for my Dad on October 19, 2024 at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Evanston, IL)

The Hideaway Alone deep in the forest, a young boy maybe nine or ten, unaware of our presence, greets a frog swimming in a pool beside a boulder. He watches captivated as it makes concentric circles in the water, while all around him dappled sunlight coming through the canopy transforms plants, stones and butterflies into colored jewels as it lands upon them.

(This scene is from a painting Dad made in 2015, based I imagine on the kind of place he always talked about - an ideal vision of solitude and wonder and a place he always hoped to return to.)

As long as I can remember, Dad loved a walk in the woods. Any bit of forest with a little wild nature would do. Here in Evanston, there wasn’t much, so on Sunday afternoons Tim, Mom, Dad and I would load into the red and white family Land Cruiser to go to Harms Woods just off of Golf Rd. in Morton Grove. We’d park in the lot, open up the hatchback and have a quick snack before getting onto the narrow trail that would lead us into the forest. Dad’s pace was always slow and deliberate, so deliberate. He’d often pause to point out a flower or rock that caught his eye or cup his ear and shush us as he tried to identify a bird only he could hear. For Tim and I, the hike through the woods was just a way to get to the water (a small canal like branch of the Chicago River) which we imagined was full of frogs, turtles and giant yet uncaught fish.

I discovered more about the source of Dad’s love of wild places a few years ago, when I recorded a long conversation with him, much of which centered on his growing up north of here in Highland Park. In our conversation, he recalled many solitary afternoons exploring the undeveloped wilds around his house, and how being sent to a “Farm School” after an accident that left him with a serious head injury was fortuitous, in a way, as it immersed him in the outdoors while other kids his age were at “inside” school all day.

Back at Harms Woods, Dad wasn’t a birder, hunter, collector or a fisherman. And as he told Tim and I, upon becoming a parent he gave up the mountain climbing of his youth where summitting was the goal. His relationship to nature had evolved, he had become an observant and patient wanderer attuned to each step without counting them and eager to share his love of wild places with his sons.

His appreciation of slowing down and of noticing the beauty and wonder all around us was I think the greatest gift Dad shared with my brother Tim and me, (and one we’ve shared with our sons Jake, Luke and Andrés.) It manifest as we grew older into camping and canoeing adventures culminating at a pristine little lake near the Canadian border called Fenske. I was tasked back then with finding a campgound for our trips from a Triple AAA guidebook and I remember choosing Fenske because it had the fewest campsites, no RV hook-ups and pit toilets, which in my calculation meant it would be a place where only true lovers of the woods and lakes would go. Although it was remote and I’m sure Mom would have chosen a spot with a few more amenities, I was right and we ended up camping there three times as a family followed by trips with friends and an epic adventure with Tim.

The Coast A frothy wave of ocean crashes over a rough, rocky shore, maybe in Maine. The wave is all white boiling foam with just a few patches of blue water. The horizon is mostly obscured by mist and only discernible through a ragged edge of sunlight. Within this swirling of tidal forces a lone seagull hovers, perfectly poised above the tumult, while below a fragile patch of red wildflowers holds onto rock about to be submerged.

In the late 1990’s about the time Dad was contemplating (begrudgingly) a transition from WTTW (the PBS television station in Chicago), he began to paint. He started with watercolors, making studies of flowers and forest paths. I remember him being serious and committed to learning the proper technique, often referring to books he’d checked out from the library for tips. It seemed heavy, burdened by the need to paint correctly, but after a 40-year career devoted to collaboration where his art was always in the service of a director’s vision, he was finally getting to express himself without compromise.

Dad continued to paint in his basement studio in Evanston and gradually his work took on new life, as he began infusing his paintings with characters and little bits of narrative. No longer was his work just about technique, now he was making stories. At first the characters in his paintings were animals: a bird, a cat or a dog were added usually in the middle-foreground, like the figures he would insert into a set design model to show scale. In one watercolor, a cat with its tail at attention wanders up a country road toward the crest of a hill to greet, we assume, something or someone approaching; while in another, a floppy eared hound, at a small-town intersection, gestures toward us as if to say, “Look…”

Gradually, as he gained confidence he told me, the anthropocentrism of his animal characters gave way, and the figures became people - most often boys of the age he was when growing up in Highland Park. When I saw these new works, I felt instantly that they were self-portraits. These paintings were like sets for the stories of his youth and the dreams he’d known. Unencumbered by the requirements of producing someone else’s tv show, he was now the writer, director and set designer of his own vision.

The Long Goodbye Under a cold blue sky, a yellow school bus speeds away from us down a snow-covered country road. In the foreground, a row of rural mailboxes and a pet German shepherd stand in the place where the bus has just picked up its student passenger. Left behind amidst footprints in the slushy snow and a dropped mitten, a boy’s best friend watches, hoping for a safe journey and looking forward to his return.

My mom (looking at the camera), grandma, grandpa and uncles in 1941

My Mom, Grandma and Betty Friedan

(first published in lawrence.com in 2006)

Last Sunday my mom phoned me, and with a flustered and excited tone to her voice said, "You're not going to believe it, there's a picture of your grandmother in the New York Times today!" My grandmother past away in 1980. She was not a public person, and as far as we know, photographs of her appeared only once in a newspaper or magazine during her lifetime. So, unless she had led a secret life unknown to the family, we had a pretty good idea what the source of the photo in the Times must have been - Occupation: Housewife

"Occupation: Housewife" was an eight-page photo essay that followed the daily routine - from breakfast in the morning, cleaning the house, doing laundry, entertaining guests, to putting the kids to bed at night - of an American housewife (my grandmother) and her family. The article, which appeared between a spread for Tyrone Power and Betty Grable's new movie "A Yank in the R.A.F." and photos (that terrified my mom, then age four) of a child victim of Nazi bombing, was published in LIFE magazine on September 22, 1941.

When I asked my mom about how LIFE chose her family, she recalled; "LIFE wanted a 'typical' American family for the article. Kankakee, Illinois, where we lived was in the Midwest, and at the time was growing fast. The reporter and photographer went to the owner of the Ford auto agency in town, Romy Hammes, to see if he knew of such a family. Romy felt his family was too wealthy for what they were looking for, so he suggested us since we lived only a couple of blocks away from him on Cobb Boulevard." Sure enough, the photo was taken directly from the LIFE article, with one very obvious photo-shopped alteration. In the original photo, my grandmother is shown "picking-up" in the living room. Around her are carefully staged props: a carpet sweeper, dust mop, trash bin, and some papers strewn across the floor. She is bending over the couch. Above her, in an oval frame, is a painting of a stern looking man with an Abe Lincoln beard. This was my great, great, great, great grandfather John Ward Amberg. The Times photo is identical except that, in place of the portrait of Grandpa John, there is a photo of Betty Friedan, author of "The Feminine Mystique."

Photo altered by the NYT of grandma with Betty Friedan in the picture frame

The article by Patricia Cohen that accompanied this 'photo illustration' was titled "Today, Some Feminists Hate the Word 'Choice'." My grandmother would probably agree, because in both cases, in LIFE and in the Times, her image was used to illustrate stories that were not of her choosing. After some consideration, my mom decided to write a letter to the editor, that would explain her relationship to the photo and how it had originated in LIFE. Below is her letter, which appeared in the New York Times on Wednesday, January 18th, 2006

To the Editor:

I agree that issuing marching orders to women today is "not helpful." To try to label women is an act of futility, making them one-dimensional when in fact most women's lives are complicated and change with time and circumstance. But I was most taken with the photograph accompanying your article, because the woman portrayed cleaning her house was my mother, Jane LeValley Amberg. As noted, the photo was taken by William C. Shrout for LIFE magazine and was originally published September 22, 1941, in a feature article titled "Occupation: Housewife." My mother was unhappy with the published article, because she was portrayed as a "typical" American housewife who cared only for home and family. Not mentioned was the fact that, with no college degree, she was also a voracious reader and a committed liberal Democrat who cared deeply about national and international issues. Our first TV was bought so that she could watch the Army-McCarthy hearings. Sixty-five years after the Life article, women still struggle with the rigid, one-dimensional labels of "stay-at-home moms" and "women who work."

Pamela Loewenstein Lawrence, Kansas

Hotspot Renaissance Man

Lawrence has a full menu of stimulating places to get a caffeine fix. There are at least eleven coffeeshops in the ten-block downtown area between 7th and 11th streets, and a place to suit just about any taste or fashion. We’ve got uptight-corporate, upscale-local, funky-hip, high school-hippy, clean-Christian, family friendly-studious, and brooding-alcohol optional to choose from. All that’s missing is the old Jennings Daylight Donuts with a .40 cup and quarter refills.

Since the implementation of the smoking ban, coffee with cigarettes is out the window. However, you are free to fire up your laptop in Lawrence’s expanding coffeeshop ‘hotspots’ Check out these caffeine dens lately though, especially the ones with wi-fi, and you are likely to find a scene more akin to a telemarketing call center than a social gathering place. Thanks to the wireless internet, coffeeshops have gone oddly quiet.

All up and down Mass. you see people transfixed by the glow of their LCD screens and wired up to their ears. Mutes to the world around them, they comment on the latest blogs or google their potential and ex -lovers. Shopping, job searching, or just wandering through the ether but often unable to make eye contact with the person right in front of them. I wonder sometimes if all this digitized stuff in the air, these virtual conversations, banner ads, and gonzo porn-cams, is scrambling our brains and impregnating the lattes and cappuccinos with a compulsion to do the equivalent of drunk-dialing via e-mail.

Lo-fi Java

There are hold-outs to the trend, those modern-day luddites, who either aren’t interested in or can’t afford the gadgets. They come to the coffeeshop to interact with living breathing humans, read the newspaper, warm up, cool down, or just hang out to see what happens. For most of these retro cats, their work is elsewhere. They can’t bring it into the coffeeshop, or they’re just trying to escape the computer they’re already tied to for eight hours a day.

When I stopped in the clean, local, and sometimes hip La Prima Tazza last week , it was about 6-4 on the side of the wi-fi titaniums. The remaining four lo-fiers were sitting at a back table. Among them, was a social worker who had gone back to school after an eighteen-year absence so he could help out the drunks and addicts he knew from his recovery meetings. He got his masters degree, but grad school didn’t turn out to be all he had hoped for. So, after graduating and getting his social worker’s license, he went back to his manual labor job where he makes twice as much.

Next to him, was a middle aged divorced father of two, who is 3 1/2 years away from retirement. After flunking out of KU, “with 24 hours of F’s” in the early 70’s, this Tonganoxie native took a job with the railroad at the Burlington Northern Santa Fe switching yards in Kansas City, Kansas. Thirty-two years of assembling and disassembling freight trains. There are worse jobs, he says, and anyway he’s got seniority now, benefits, and soon a pension.

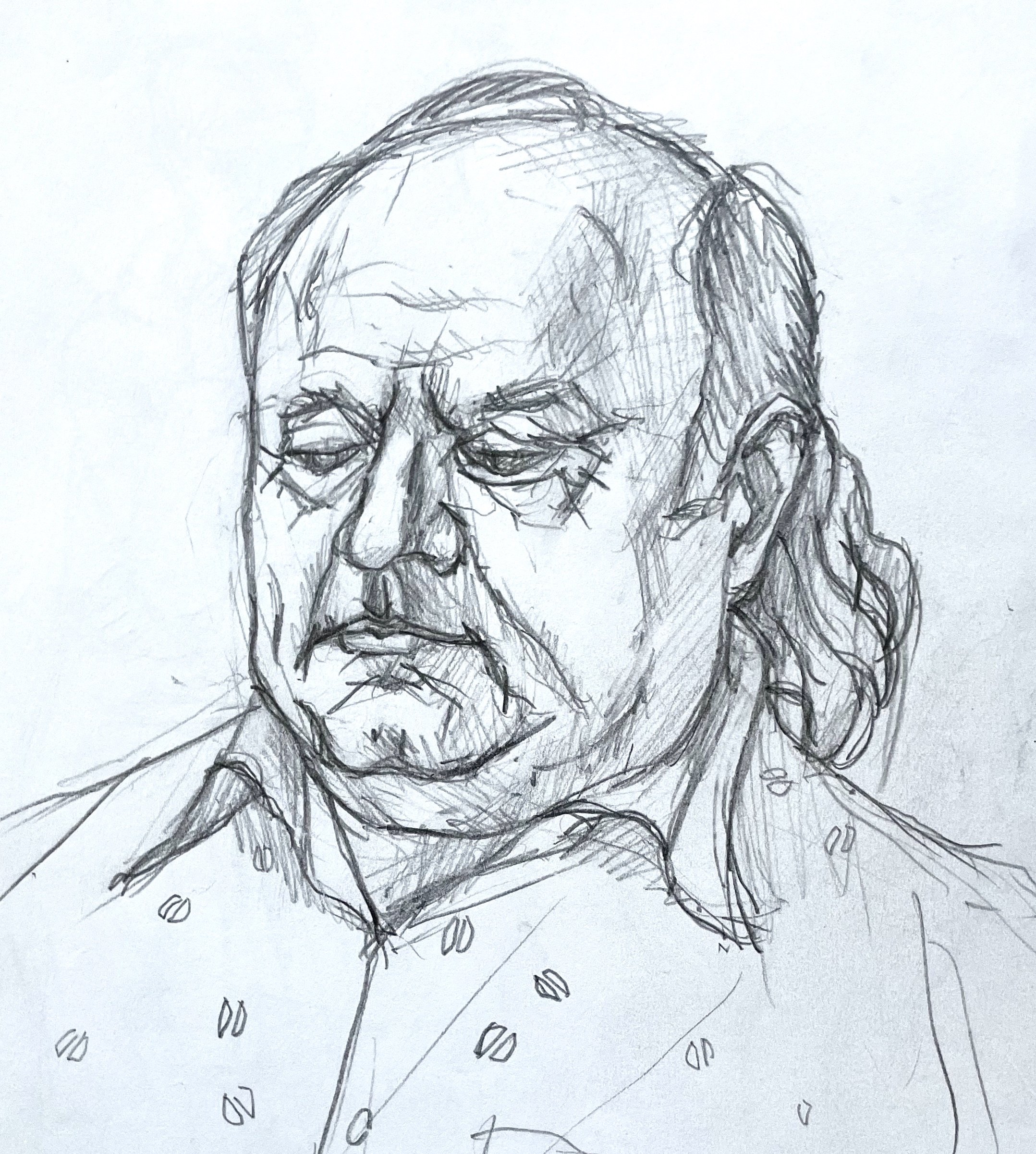

Across the table, looking a little like Ben Franklin with long hair where it still grows, was a thirty-year veteran of the Lawrence music scene. Among the bands he fronted back in the pre-MTV days, were the Rumblebugs, Circuit Breaker, The Spiders, Good Question, The Tonganoxie Red Water Band, and Scuzbucket. He was just out-front sitting on a bench with his guitar, playing songs from his new CD “The New Swirl Sound” for an audience of passersby, dogs tied to parking meters, and smokers in front of Liberty Hall. Looking at him, you’d expect a rough and weary voice, but what comes out is more like a cross between Buddy Holly and Elvis Costello.

And sitting in the corner, there was the requisite coffeeshop artist. That sneaky looking guy always scribbling in an oversized black book, and never showing anybody what he’s doing. At the back table, the ex-social worker, railroad man, and musician tolerate him. They tolerate his moodiness, and how he spreads his fishing tackle box full of art supplies, portable lamp, three drinks, and the current panel of his epic graphic novel “Zinky Evans and the Spiritual Time Machine” across the table they’re trying to share.

He’s been drawing comics since he was in high school, when his dad used to berate him with advice like “You’d be better off buying a box of rubbers than that Mad Magazine.” A student of the great masters of art, his comics are a post-modern mix of figures from classical sources with characters inspired by his comic book heroes Wally Wood and R. Crumb. The semi-fictionalized accounts he creates about his life and work are in the vein of graphic novel memoirs like “American Splendor,” the difference being that he does both the writing and illustration of his story.

Jim-of-all-Trades

Some of you are probably wise to my conceit here. You’ve put it together that these four guys at the back table , the comic book artist, veteran musician, railroad man, and minor league social worker are actually embodied by one guy - the coffeeshop regular, jack-of-all-trades, neo-renaissance dude, Jim Lee. Jim is a lo-fi kind of guy, but he isn’t averse to technology. He plugs in his Gibson to a little amp out in front of the coffeshop in the summer, and he’s even got a website where you can hear a few of his latest tunes and check out pages from his comics. Jim says he comes to the coffeeshop to get out of his head so he can work his art, maybe stumble into a good idea, or chat about the weather and the world with whoever shows up.

Jim is the real deal. He considers himself an artist / musician who pays the bills working for the railroad. No Sunday painter, Jim is one who does art to live - as opposed to make a living. He doesn’t make money from his art, rarely shows his work, and although he no longer plays the bars or has his own band, he is as passionate today about his art and music as he ever has been.

In the published correspondence “Letters to a Young Poet” between a young German soldier and the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, the soldier asks if his poems are any good. Rilke replies, “A work of art is good if it has arisen out of necessity.” Jim Lee’s songs and comics are just that, as necessary to his well-being as the sun is to a healthy garden or people talking about the weather are to a good coffeeshop. (originally published in the lawrence.com deadwood edition in 2006)

from Henry’s coffeeshop

Take a Penny, Leave a Penny

(This piece originally published in 2012, comes from my project Give Take Give, which explored the gift economy and social network connected to the Social Service League dumpster in downtown Lawrence)

Coffee and a bagel, $4.97. I handed over a five-dollar bill, got three cents change and put the coins in the little ceramic dish next to the cash register - a small gift for a future patron who comes up a few pennies short. The next time it may be me who needs the help, and without a second thought I'll reach into that same dish. In a very unscientific study of coffee shops along Massachusetts St., I found that all five of the locally owned ones I visited maintained penny dishes, while the two corporate chains I checked did not.

It's a modest convenience to help make change and keep the wheels of commerce turning. It's also a form of gift exchange that operates right next to the cash economy. As pennies lose buying power (Canada minted its last one cent piece in 2012, and many in the U.S. have called for the end to the penny here), they are easier and easier to part with. But imagine, if there is, let's say, just $20 in change that circulates through these exchanges in Lawrence in a week, that would mean $1,040 in a year, and literally millions circulating freely across the country, from those with more than they need to those who don't have quite enough.

All of us who give and or take a coin or two are participating in a kind of 'pay it forward' economy predicated on trust (there are no explicit rules for how many coins we can take) and long-term reciprocation (we can imagine that one day we will be the ones in need). This begs the question, if we can freely exchange pennies, nickels and dimes, why not other things like food, housing and education?

(Since I wrote this, the exchange of currency (dollars and change for goods) is rapidly vanishing, replaced by cards and payment apps on our phones. A consequence of this shift is that increasingly we are prompted by payment screens to tip or “round up” when we purchase something, while penny dishes disappear as fewer and fewer people carry change of any denomination let alone pennies in their pockets.)

The Percolator’s - International Paper Glider Fly-In

My son Andrés is six, and high on his list of things to do these days is throw stuff, preferably objects that can go a great distance and/or can break, dislodge, dent, shatter or otherwise have a big impact. Wonder where he got this passion? When I was six, one day I spent an afternoon seeing if I could throw a rock and hit a taxicab driving by our apartment. Timing my throw was crucial and I succeeded. After being grounded for a week, my mom bought me a baseball glove, jump starting my pitching career.

To help direct Andrés’ enthusiasm and minimize damage, we’ve been making a lot of paper airplanes. I know a few basic designs, we have a pretty cool book that has instructions for more advanced models and we improvise. Then we do test flights to see which ones fly the farthest or do the coolest stunts, which led me to showing him photos from the 2010 Lawrence Percolator International Paper Glider Fly-In.

The Fly-In was a part of the Percolator’s “Out of Thin Air” exhibition and was held in the lobby of the Lawrence Arts Center. Glider pilots, young and old, designed their crafts to excel in categories including: Distance Flown, Time Aloft, Surprise, Best Crash, Trickiest, Decoration, Weirdness, Launching Technique, Unusual Design, Elegance and Helicoptering.

Tiempo de la Tierra - the Zine

Here it is, the chance to add your own colors to the Tiempo de la Tierra mural! Feel free to print these at home or pick up a few at Cottin’s Hardware Store, 1832 Massachusetts St.

Connections

In 1978, there was this great show on PBS called “Connections” where amiable host and historian James Burke began with one simple idea, act or circumstance and then followed its consequences through time usually to some dramatic change in human “progress,” like how the need for a brighter light for surveying (known as “limelight” for its use of quicklime as the element) led to the invention of motion pictures. As a twelve-year old just starting to explore my own connections to the world, this show blew my mind.

If you think about it, “Connections” big picture view of change has a more modest analogue in our own lives. Every now and then, we can trace an inspiration, big decision or a path not taken to a chain of circumstances chosen or encountered that led us along a path unforeseen at the time. Always backwards of course since without the assistance of a good Tarot reader it’s hard to know what will come from our actions, although perhaps sometime soon AI will be able to predict our futures.

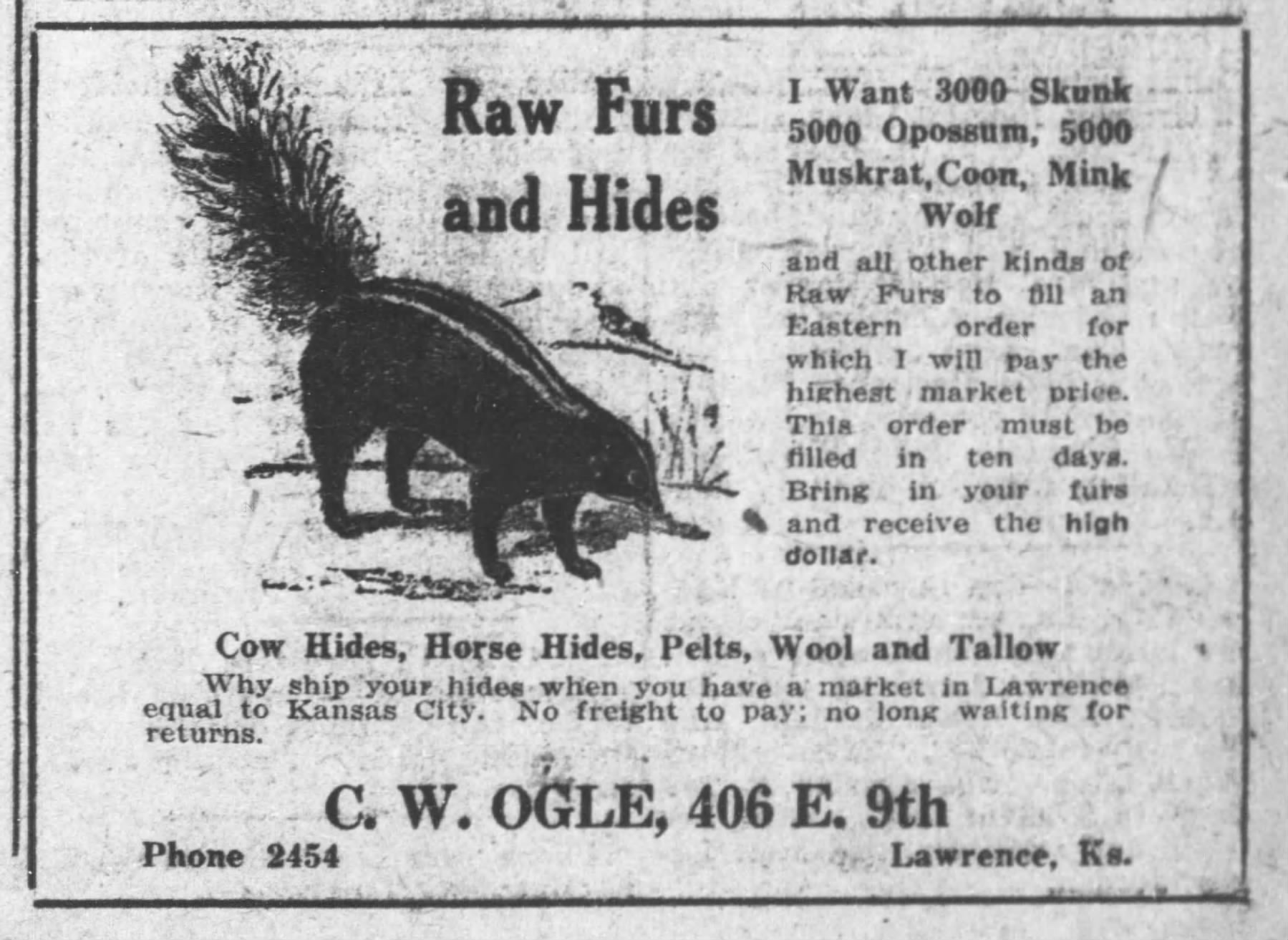

Sixty-eight years ago, a local auto mechanic looking to establish his own shop set in motion a chain of events that in this case would lead to a big change in my life. Unless you’ve built your own workplace, where you labor, its history, previous tenants and uses may be a mystery. (The remarkable new documentary “Occupied City” by Steve McQueen explores this idea). While some places honor their origins, most keep their stories hidden under generations of forgetfulness (sometimes willful) and layers of paint, and when the connection to a place is lost, when the chain is broken, there is no reason to wonder, no desire to preserve, and no story to tell or add to.

For years, after moving into my studio at 411 East 9th St., people would ask what the building had originally been built for. I had only been aware of the previous tenant, Micro Resources, that repaired electronic and computer gadgets, and a brief period when some auto detailing was happening as evidenced by the checkered flag paint job on the windows. For me, it was an old garage with a leaky roof that allowed me to reinhabit the living room in my apartment after years of using it as a studio.

Some years later, a guy walked into the studio with a pair of kitchen cabinet doors. He said he was looking for Lawrence Custom Woodworks, which I discovered had occupied the space from 1989-1996. Others walked in looking for friends, Joe D came in more than once looking for a bike pump, but no one ever came by with a pelt, raccoon, possum or otherwise, although Will Ogle told me they would have been in the right place between 1922-1953 when his family’s business, Ogle’s Furs, was in a small building on the same site. Still, I had no idea who built the garage and why, until a few years ago when I posted an invitation to a studio open house and received a response from Carol (Proctor) Guy. Carol knew well the origin of the building, because her dad, Les Proctor, built it in 1955.

For Carol, that old garage was the realization of her dad’s dream to become his own boss and own his own business. Les had worked on WPA projects, been a butcher, worked at Sunflower Ammunition and operated a gas station in North Lawrence before building the garage for his own auto repair shop and, forty-two years later, my studio.

And while Les could not have known that one day a muralist would find his footing because of that building, if he had not built it, I’m pretty sure that the trajectory of my life and work would have taken a different turn. Dave the farmer? Dave the public-school teacher? Dave the grocery store assistant manager?

Les Proctor

Learning the building’s origin and how a family’s desire for a place of their own connected to my dream of becoming an artist and revealed stories that had always been there but had been invisible to me. It reminded me that every place and every person I encounter is filled with and marked by their own stories which only become apparent by getting to know each other, and that the act of forming those relationships will seed new connections and have profound consequences that we can hardly imagine.

Thanks to Carol Guy and Bob Proctor for sharing their stories with me. And thanks to Les Proctor for building his shop.

The Last Days of 411

This week, twenty or so folks have been making catrinas (paper mache figures) for Día de los Muertos in my studio at 411 E. 9th Street. Organized by Somos Lawrence, kids, parents, grandparents, tíos and tías are seated along a table that runs the length of the building. There’s hot coffee, donuts and music to keep the team going. The artistas began during the last warm days of autumn with the big garage door rolled open and are now buttoned-up inside after our first deep-freeze.

This community workshop will be the last for my studio at 411. By the end of the year, I will have moved, what I can’t give away, to a new studio about ten blocks west. The new space , the renovated garage of my mom’s old house, is really not that far away, but I recognize as friends have told me that closing down 411 will mark the end of something for me, for East Lawrence and for our arts ecosystem.

I moved into the studio in 1997, at the same time I was leaving my last day job as a Wheatfields baker and beginning to work as an artist full-time. It was a dilapidated old building being used as an electronics repair shop and, with floor to ceiling parts and wires, it was hard to imagine it’s potential when I first walked through. The building was originally built by Les Proctor as his auto repair shop in the 1950’s and has stood witness to how the neighborhood has changed and adapted. At the time, renting such a big and expensive (for me) space felt like a gamble. I would have saved money maybe if I hadn’t, but I also would have missed all the things that have kept me rooted here in Lawrence.

Together, over the years, passersby, local artists and fellow travelers co-created a new home for imagining that hadn’t existed in Lawrence for a long time. It’s been and incubator a percolator a third space a hide-out a headquarters a club a crash-pad a haven a hangout a launch-pad a project space a refuge and an info shop. From the early days of the Percolator and Seed lectures, to the US Department of Arts and Culture Field Office and the many campaigns, protests, marches, and exhibitions that found a home there, 411 has been a dream come true for me – a place to make things happen.

I know that new spaces that suit the needs and desires of local artists and their comrades will emerge (they probably already exist), but I still feel an ache in my gut that goes with leaving and letting go. I’m grateful for the folks urgently working there today. (You can see their finished work on Thursday, Nov. 2 in North Lawrence) They remind me just how special the studio has been over the years. Homegrown independent non-commercial. Spaces like this are essential to artists and activists. They expand our spatial imaginary (what’s possible) while supporting experimentation and frivolity.

Thank you to all who have shared 411 over the years. It’s been a joyous ride.

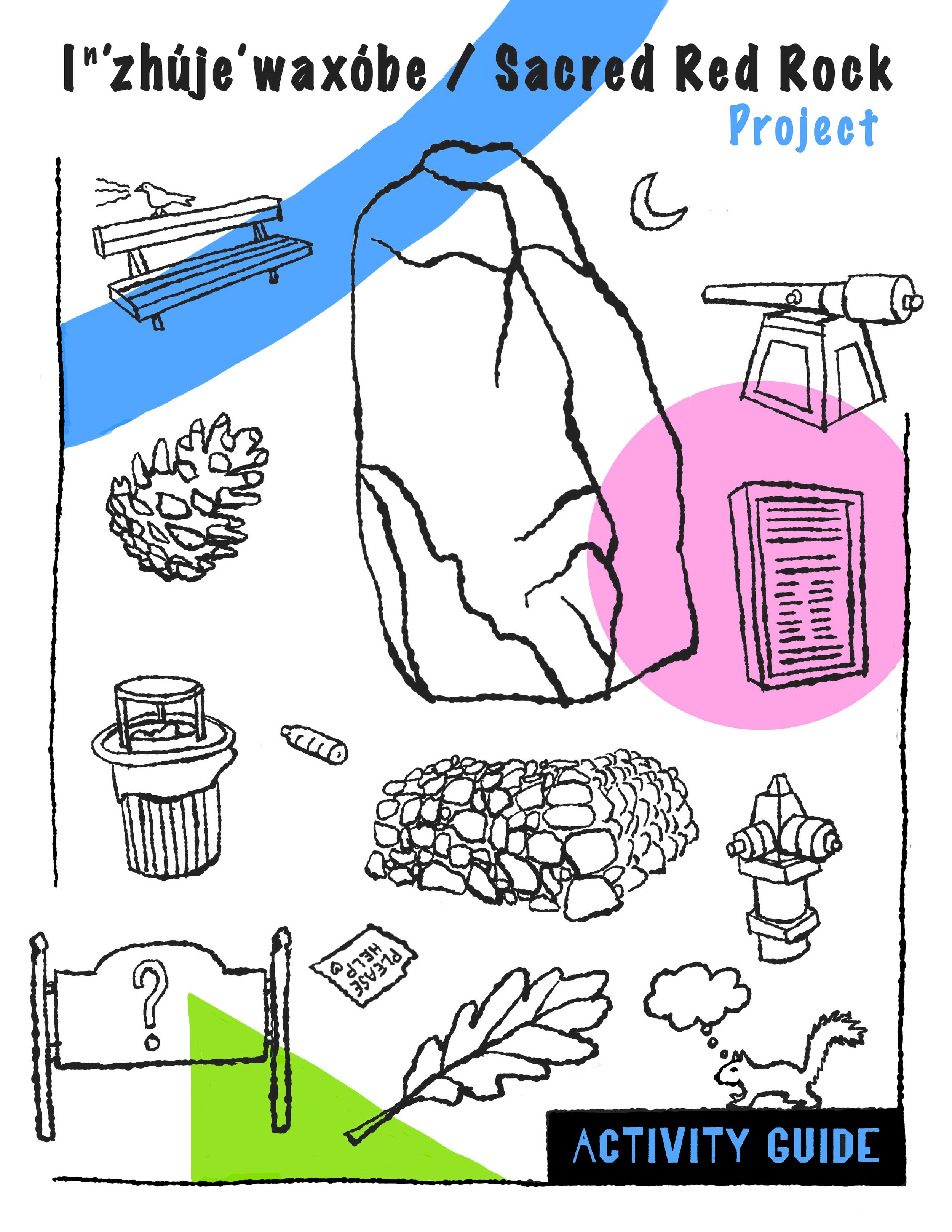

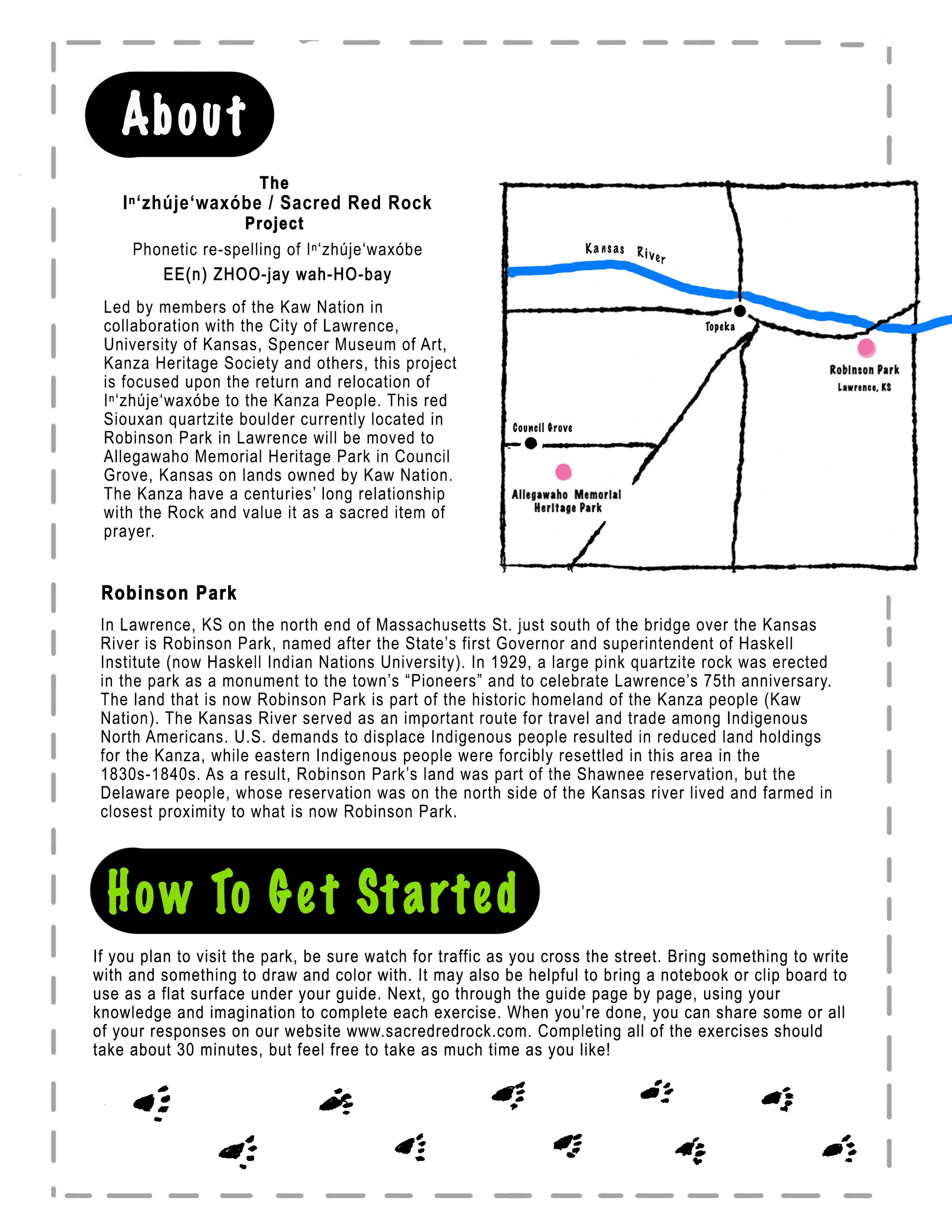

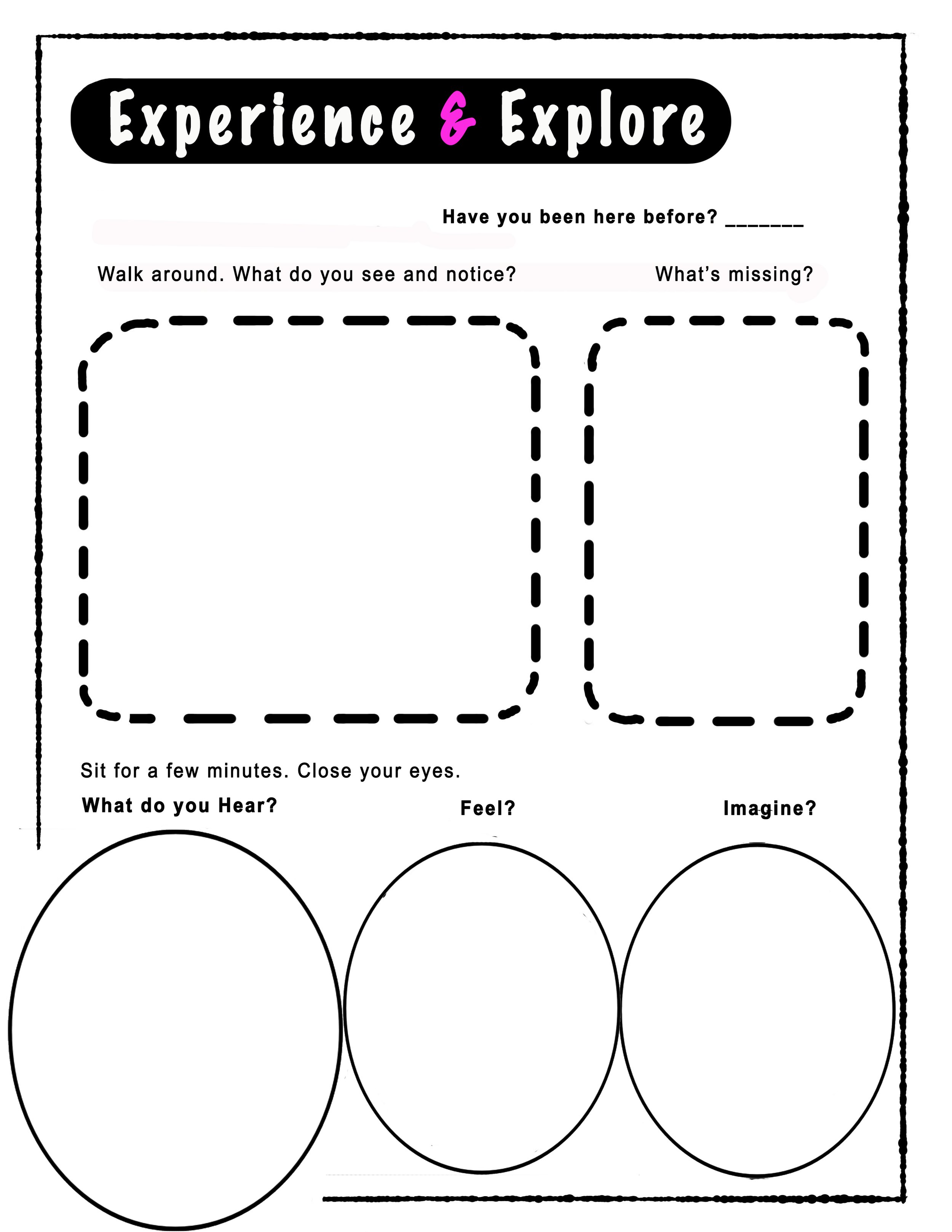

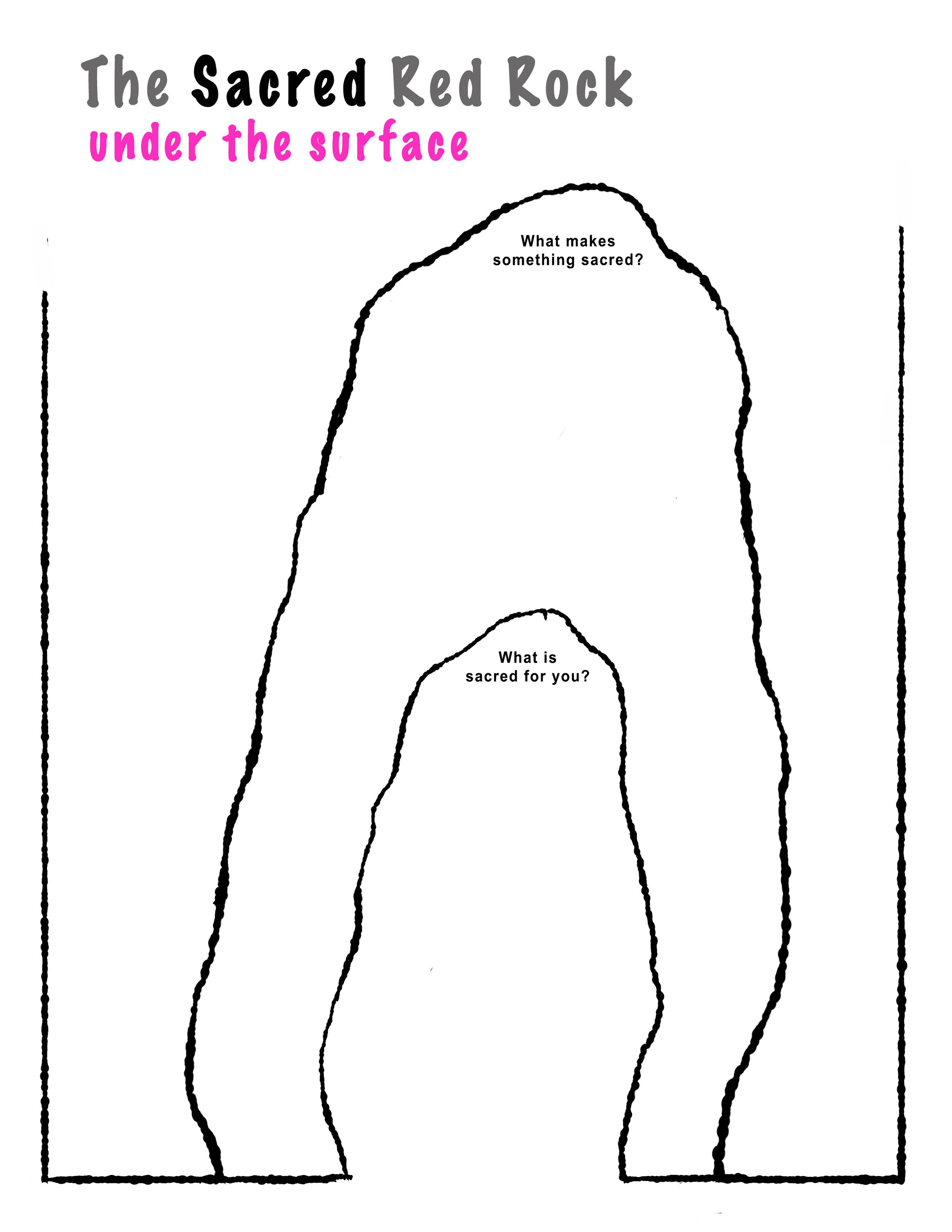

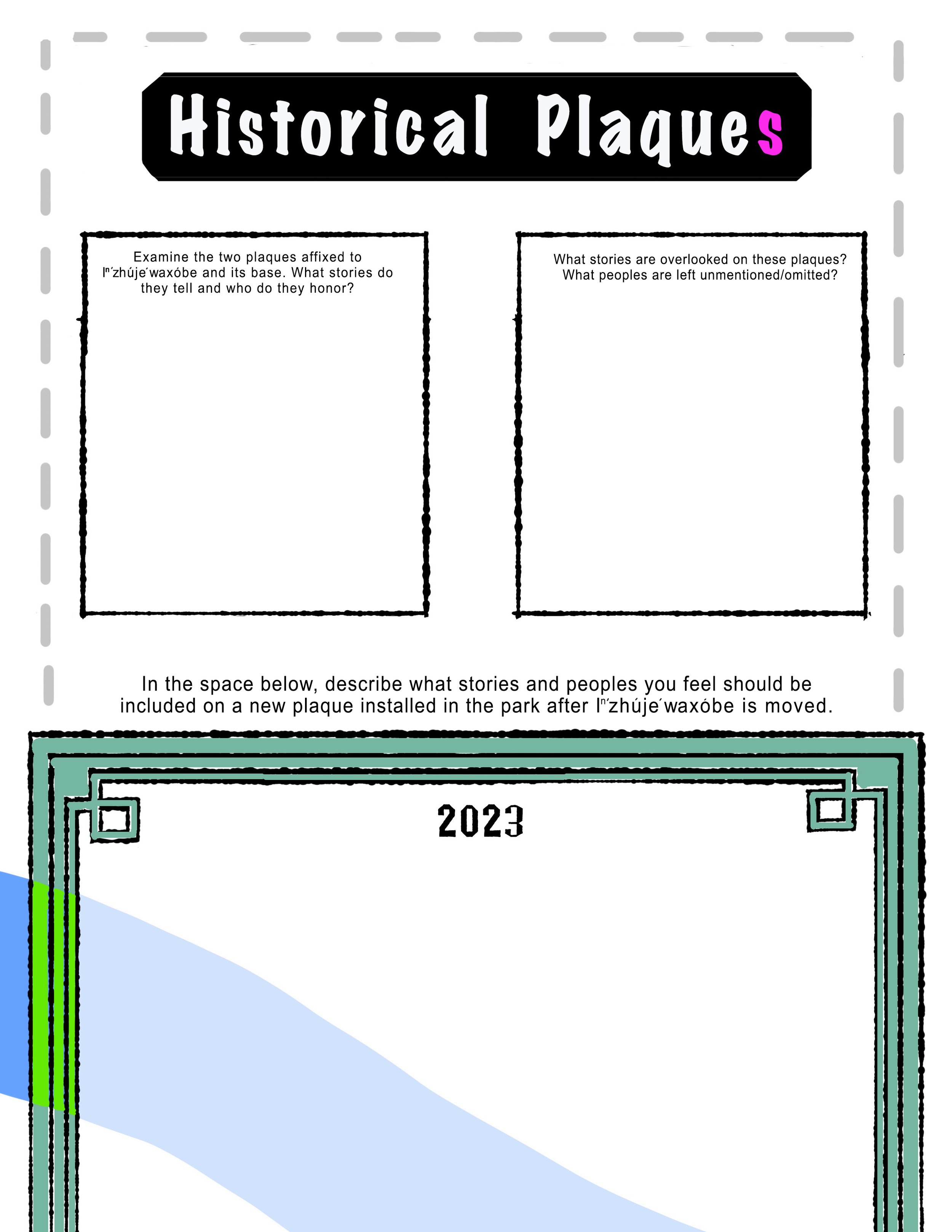

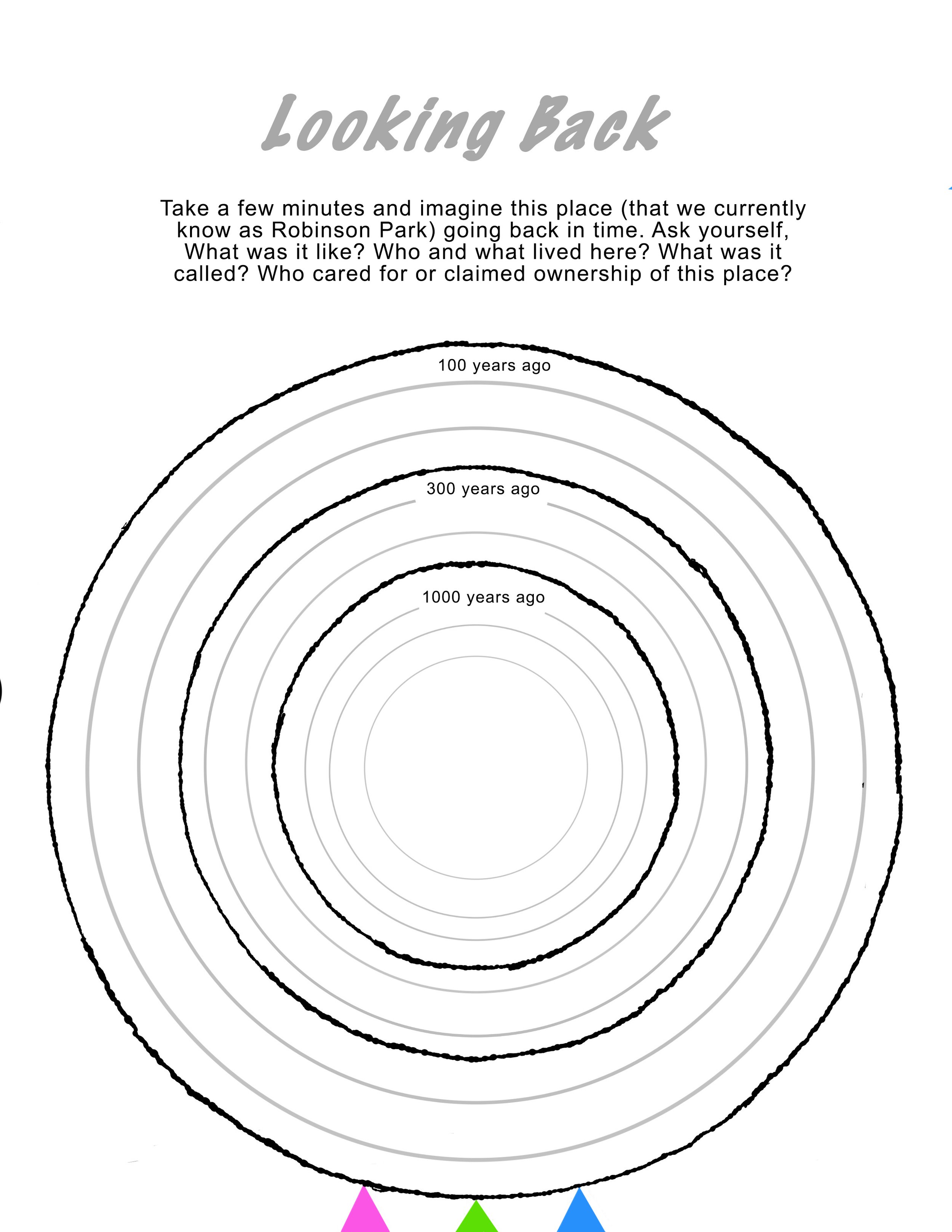

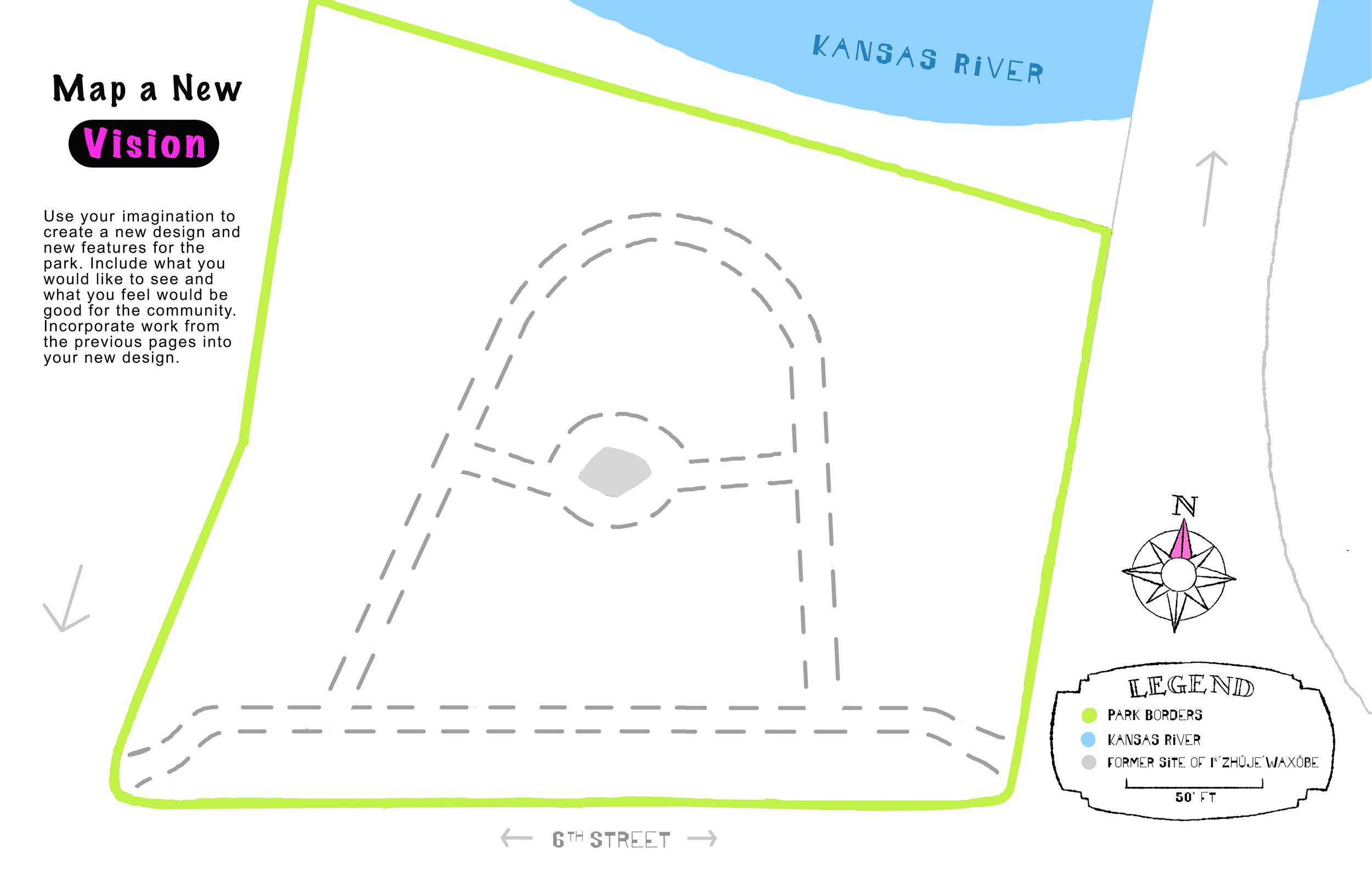

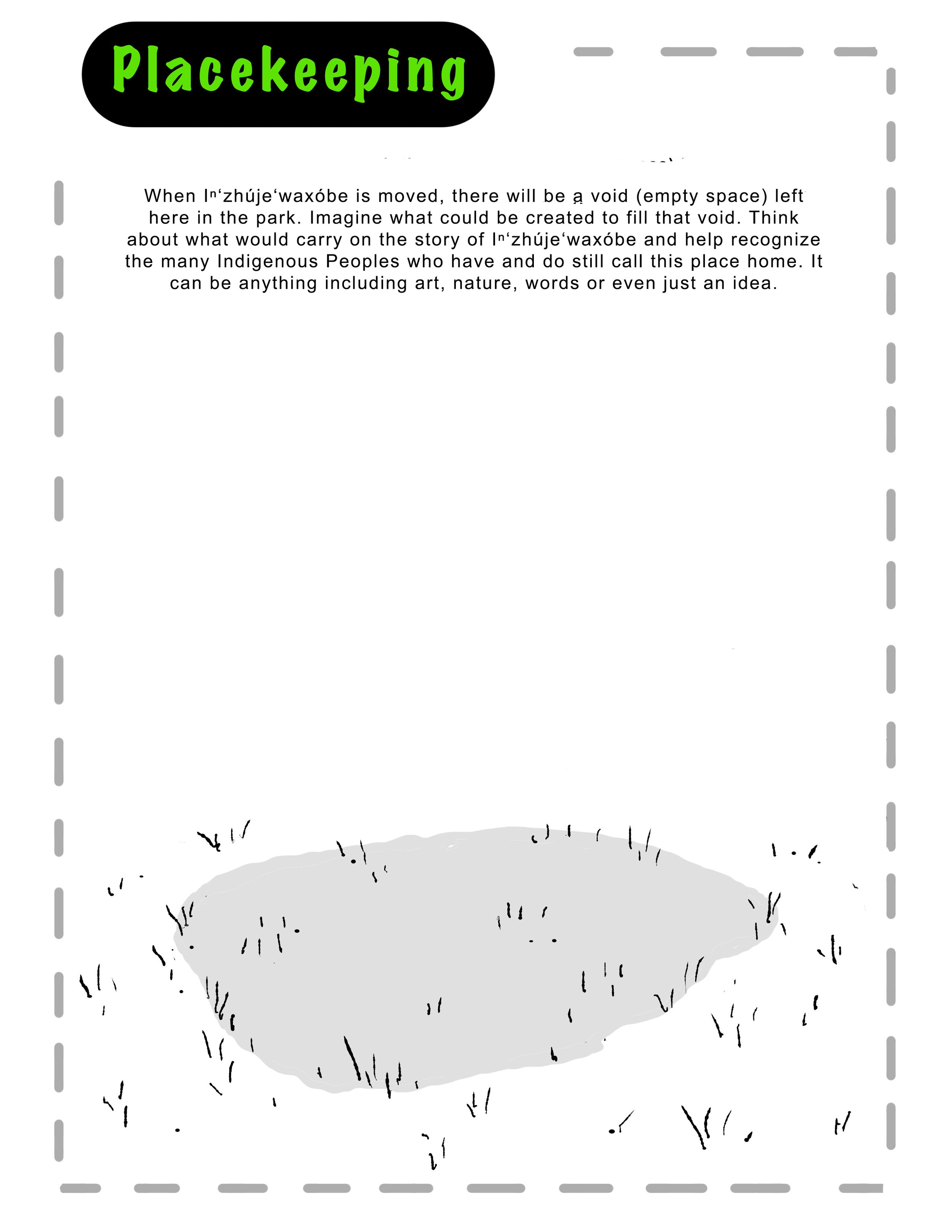

Iⁿ‘zhúje‘waxóbe / Sacred Red Rock - Activity Guide

As a part of the community engagement efforts for the Iⁿ‘zhúje‘waxóbe / Sacred Red Rock Project, I designed this activity guide for folks to use as a way of exploring the history, geology and future of the Sacred Red Rock and what we now call Robinson Park. You can download and print your own here, or pick up a hard copy at Tommaney Library at Haskell Indian Nations University, Lawrence Public Library, Spencer Museum, Watkins Museum or City Hall. And, it’s not just for kids, I wrote and illustrated it for a wide audience. See for yourself :)

The Lawrence Community Garden Project

(In 1991, there were no community gardens in Lawrence. Today, there are more than twenty. This is the story of how one of the first got its start.)

In January 1991, I moved to Lawrence to attend grad school a few months after finishing a farm apprenticeship in upstate New York. Farming had been a detour from my art education and possibly a new path. Up until then, I had been making dark and foreboding paintings and prints of small towns and their adjacent rural landscapes in Iowa and Indiana where I’d been in school. But in the spring of 1990, I had a realization that for all my concern about the Farm Crisis, and heartfelt depictions of places being gutted by it, I really didn’t know much about agriculture, big or small. So, with no job lined up and no commitments, I made a phone call (pre-internet). I found the number in a book at Platypus Bookshop in Evanston, IL while visiting home that complied descriptions and contacts for a host of “alternative jobs,” things like working on a fishing boat, teaching English in a foreign county, and farming.

Rose Valley Farm

The number was for Rose Valley, an organic farm and home of the New York Garlic Seed Foundation just south of Lake Ontario near Rochester. After a ten-minute chat with farmers Liz Henderson and Dave Stern, where they mostly asked about my capacity for hard physical labor and my politics, I got the job and soon packed up my Corolla to head east for the summer. My time at Rose Valley opened me up to a new world. The hard physical labor. The belief that Dave and Liz held about making sure their prices were accessible to working class people. And the directness of it all – how there was no second guessing about whether not the work we were doing was good or useful. I learned that it was a Sisyphean task to keep the farm going year to year as big growers were starting to go organic, and grocery chains like Wegmans were starting to offer corporate organics alongside that of local farmers.

When I arrived in Lawrence a few months later to pursue an MFA in Painting at KU, I was more focused on continuing my Ag education than art, and immediately sought out a farm job. At the local co-op across the street from my apartment on 7th St., I saw the contact for Wakarusa Valley Farm run by Mark Lumpe. I called him and soon I was picking rocks from the fields, planting salad mix, and helping Mark put plastic over the frame of his new greenhouse.

Sign I made for Wakarusa Valley Farm

I worked with Mark for a few months before I asked about leasing an acre to try my own thing. We had talked about starting a little CSA like the one at Rose Valley, where people came to the farm to work for an hour or two a month in exchange for produce. He liked the idea, but the more I thought about it, the more I realized it wasn’t going to work. I would have to commute to and from the farm while trying to finish grad school and keep my other job at the Lawrence Lithography Workshop.

In the early 1990’s, WWOOF (World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms) programs were getting popular, and urban farming was just beginning to blossom again, 50 years after the “Victory Gardens” of WWII. The time felt right and I thought If I couldn’t start a CSA at Mark’s I still wanted to do something that combined my interest in farming with a vison of collaboration and community. It was that desire that led me to community gardens. A visit to the library gave my interest a direction and a template. I found a book about the Boston Urban Gardeners (BUG) which outlined the step-by-step process to organizing and establishing a neighborhood community garden. Voila!

I shared my idea and the BUG book with a few like-minded friends who got on board right away. We put up posters around town announcing our first meeting and began to look for a suitable site for the garden. After talking with folks at the City, we found a spot that seemed perfect, a half-acre below the Kansas River bridge in an unused part of Constant Park. We worked out the logistics with the City and got liability insurance, and in the Spring of 1993 received permission to begin our garden. And then… as many will recall, there was a flood. If you’ve ever walked the river levee, you may have seen a small sign among the rocks that marks the high-water mark from that summer. Needless to say, Constant Park went from the perfect spot for our garden to being six feet under water. We’d have to find another site. In the meantime, our group began the process of getting non-profit status in the hopes that having it would give us some legitimacy and a few more fundraising options.

Me as the Co-op produce manager in 1993

Our fallback after the flood was a grassy lot adjacent to the new home of the Community Mercantile Co-op at 9th & Mississippi. I had just started working there in the produce department and discovered that the lot was being maintained by the Co-op since both properties had the same owner. We presented our community garden vision to the Co-op board of directors. They resisted initially, worried they would lose the few bucks they were making off of parking during KU football games.

While we waited to get our approval, a couple of us were able to grow a test plot on the space, mostly greens, basil and tomatoes, and got the soil tested. And we explored possibilities for the garden layout and began designing the garden handbook. The layout of the garden was straightforward with individual plots, common areas, a gathering place and a tool shed (later we built a greenhouse). We didn’t need much in the way of money, but we were able to get a CDBG grant through the City which covered our liability insurance, a few tools and supplies to build a fence. The Co-op provided water via a very long hose.

When we were finally ready, we had a local farmer haul his little tractor over and begin to break up the compressed soil. Then we trucked in about 25 loads of composted manure from the horse stables that used to be where the 6th Street Wal-Mart is now. And then we planted. We had families, single folks and students all gardening together. We gave workshops and partnered with arts groups, and then in our second year we began our harvest festival. We closed off the alley and had live music (Al Trout and the Hokum Washboard Band), a chili eating contest, egg toss, food made from the garden and craft booths. It was a blast!

We also started selling produce to the Co-op, an arrangement inspired by the new (at the time) garden/market in Kansas City called the Blue Bird. We even had an occasional booth at farmers market to sell produce and share information about the LCGP. The garden thrived. I helped coordinate it for about ten years (until my schedule as a muralist kept me out of town too much) and I continued to have a plot there until 2017.

The LCGP’s 30th anniversary will be next year. It became more than we could have ever imagined. Not just a place to grow food, but also an improvised gathering space where people from different walks of life met, worked together and made friends. Thanks to all the folks who continue to care for this little gem. It’s heartwarming to see that its spirit continues.

The LCGP garden in 2003

A Culture of Possibility

Earlier this month, I had the pleasure of talking with Arlene Goldbard and Francois Matarasso, two of the most thoughtful and insightful writers about the field of Community-Based Art, for their podcast, A Culture of Possibility. You can listen to our conversation here. You can also read Arlene’s blog post introducing the episode here, and Francois’ piece about my 2006 drawing, “View From East Lawrence,” here.

Ukraine Peace Flag

Save Our Schools

(Special thanks to Lindsey Yankey for sharing her schoolhouse image for this poster)

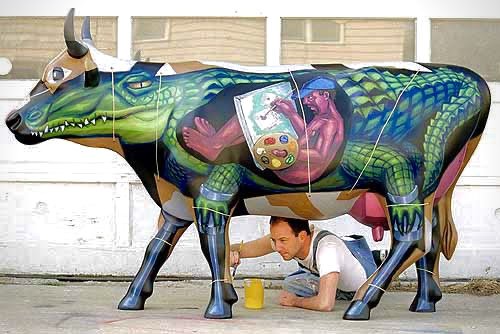

Dave painting “Celebration of Cultures” in 1995

Celebración de las Culturas, 1995 & 2021

Twenty-six years ago, when I was twenty-nine, I was working at the Community Mercantile as produce manager and just beginning to make murals. At that point, I really hadn’t figured out how I wanted them to look - what visual language would best suit my skills and aspirations. I poured over images of Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros’ murals and tried to imagine myself in their shoes. It was tough. Their mastery felt unapproachable. Searching for inspiration, I would spend evenings at the library hoping something would catch my eye. One night, it did. I pulled “Jacob Lawrence: American Painter” off of the shelves and immediately was struck by the cover.

I had known Lawrence’s early work like his Migration Series from the 1940’s, but I’d never seen what he made later. I checked out the book and began working on drawings inspired by Lawrence’s images of builders and families. Later, I would learn that one of Lawrence’s heroes was Orozco. It made sense. Of the Tres Grandes, Orozco’s approach was closest to Lawrence’s, and it turned out that they had even met once while Orozco was working on a mural at MoMa. Adapting my drawing style felt awkward at first, too imitative and not enough my own. It took time for me to find my own way of seeing shapes within a form and using color not only to describe an object, but to create a feeling and sense of place.

The real test came when I was asked to lead a new mural project for the annual Harvest of Arts Festival in downtown Lawrence. The theme was “celebration of cultures.” Painted with dozens of volunteers in October of 1995, it was the first mural I’d made after incorporating my studies of Lawrence. Last week, I brought it back to life with a fresh coat of paint.

Lawrence's chapter in the new Routledge Handbook of Placemaking

Folks here in Lawrence probably remember the heated debate about East 9th Street and the Arts Center led project that aimed to transform it into an “arts corridor” under the banner, Free State Boulevard. My personal account of that project is now a chapter in the just published, Routledge Handbook of Placemaking.

My involvement began last spring when I was invited by one of the book’s editors, Tom Borrup (Tom had been to Lawrence in the midst of the E. 9th project as a Cultural Planner hired by the City), to share my story for this remarkable new study which looks at the concept and practice of placemaking from an international perspective. Having endured the years-long struggle, first as a critic and later as one who helped shape the project that was implemented, I took the challenge. You can read my essay here. Below in an excerpt.

Adjacent to present-day downtown, East Lawrence gradually slopes down to the railroad and old factories that run along the Kansas River. It’s still full of small single-family homes and backyard gardens. It’s where Langston Hughes went to church as young boy, where Civil Rights marches began and ended and more recently where a massive creative placemaking project funded by ArtPlace was proposed to revitalize us. That project, known as Free State Boulevard is the subject of this essay. As a first-hand witness, I was a participant in fighting the project and in the end one of the people who reimagined it as a more just and equitable endeavor.

On Thursday, June 17th, 2021 contributors to the book responded to provocations and questions from, self-proclaimed interloper, Roberto Bedoya. Watch the video here - Practices of Placemaking: affect, antagonism, attachment

Joplin, Ten Years After the Tornado

Ten Years ago, I was preparing to begin a new mural in Joplin, Missouri. Plans were well under way, funding was secured, when on Sunday, May 22nd at about 6pm Joplin was hit directly by an F-5 tornado. Damage was almost incomprehensible. One hundred and sixty-one people were killed. Thousands were injured, and thousands more displaced. In the immediate aftermath, our mural team reached out to new friends in Joplin to see if they were ok and to see what they needed. Only later, did we consider if or what our mural project might be like in light of the tragedy. The story of that experience is beautifully documented in the film “Called to Walls” and the mural that we did do with hundreds of residents still stands today on the corner of 15th & Main, a mere two blocks from the path the tornado had taken. Below is an essay I wrote for the Joplin Globe in September of 2011, on the occasion of the mural’s dedication. I share this in memory of those who were lost, those who survived and those who met the moment with love and generosity - especially the wonderful Jo Mueller, Director of the Spiva Center for the Arts while we worked on the mural.

‘The Butterfly Effect’

by Dave Loewenstein

If you had asked me a year and half ago what I’d be doing right now, I doubt I would have given this answer: “Painting butterflies on a wall in Joplin, Missouri.” But here I am, along with what’s now been more than 300 Joplin volunteers, engaged in a challenging and wonderful project painting a giant mural on the Dixie Printing building at the corner of 15th and Main streets.

But why make a community mural here and now? What makes murals different from other art forms? These are questions I often hear at the first community mural meetings. My answer usually starts with this quote:

“The highest, most logical, purest and most powerful type of painting is mural painting. It is also the most disinterested, as it cannot be converted into an object of personal gain nor can it be concealed for the benefit of a few privileged people. It is for the people. It is for everybody,” Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco (1883-1949). I like Orozco’s quote because it distinguishes murals from other types of painting, and puts them in a field more closely allied with collaborative arts like theater and music, which for the most part are not hidden away and are rarely considered objects to be bought and sold.

This is important to me because our mural projects — and Joplin is a good example — are at their heart an exercise in collaborative community action where the finished work is important, but is not the only goal. Writer Arlene Goldbard, author of the book “New Creative Community: The Art of Cultural Development,” says, “Someone taking part in a collaborative theater, for instance, is able to have a very full and rich experience of citizenship: to be one among many whose ideas and efforts are welcomed equally, who pursue common aims in a climate of respect and affection, who together make something meaningful to themselves and the whole community. Even in a dark time, this experience foreshadows true democracy and full vibrant citizenship.”

And here in Joplin it was apparent when we visited in early June that residents were focused and sincere when it came to discussing issues of history, identity and a vision for the future, all of which would be essential in creating a meaningful and resonant mural. Young people have been especially candid and expressive. We worked with more than 200 children at the Boys & Girls Club, YMCA and Spiva Center for the Arts making drawings about their idea of “home” in preparation for our mural.

Drawing with kids is illuminating. Kids, up to a certain age, draw the way grown-ups sing in the shower — full-force with heart and emotion and with little concern for how they sound to others. This is especially true when you give them just enough of a prompt to get their wheels turning and then get out of the way. The drawings Joplin’s youths made are remarkable — remarkable for their beauty and their honesty, and remarkable for the way they examine and illustrate the joy and sorrow of living in a time of confusion and contradiction on one hand, and unparalleled community spirit on the other.

Like a visual poem, the drawings created by these young people and their older counterparts on our design team form the heart of our mural. It’s a mural we’re calling “The Butterfly Effect: Dreams Take Flight.” I could try to describe the mural, but you can go down to 15th and Main streets at 2 p.m. today for the dedication and see it for yourself. That said, here’s a sort of caption that might be written under a photo of it in the future:

Inspired by the metamorphosis of butterflies, the myth of the Phoenix, and the capacity for renewal expressed in the imaginations of children, the design is like a short picture story in three chapters.

In the far-left panel, a miner standing atop giant crystal formations points out toward the future and a young George Washington Carver examines the roots of a plant specimen. Above the figures is the first part of a quote from Langston Hughes’ poem “In Time of Silver Rain.”

In time of silver rain

The butterflies

Lift silken wings

To catch a rainbow cry.

Dividing this panel from the rest of the mural is a large serpentine shape taken from the Wilders Restaurant neon sign on Main Street. To the right of the Wilders sign, two children sit at a table drawing. Their pictures activate an imaginary landscape that unfolds in front of them, beginning with a small butterfly that floats above the surface of the wall. At the center of the mural, images made by children in our drawing workshops depict cleanup activities after the tornado. After the challenges of the storm, new flowers bloom, trees sprout new leaves, and children come out to play. Butterflies float magically over the surface of the mural carrying its images within their wings.

In the far-right panel, divided from the imaginary landscape by a neon sign inspired by Wilders Restaurant, eagles carved from tree stumps downed during the tornado are illuminated by the light of a Phoenix that has taken flight. Inscribed above the Phoenix is the second part of the quote from the Langston Hughes poem “In Time of Silver Rain.”

And trees put forth

New leaves to sing

In joy beneath the sky.

This short description pales in comparison to seeing the mural firsthand, so please come visit us as we add the final touches. Thank you Joplin for working together with our mural team with such serious purpose and for being such gracious hosts. I hope the mural we have created together will inspire others. You have many great stories to tell and many big walls calling out for a little color and imagination.

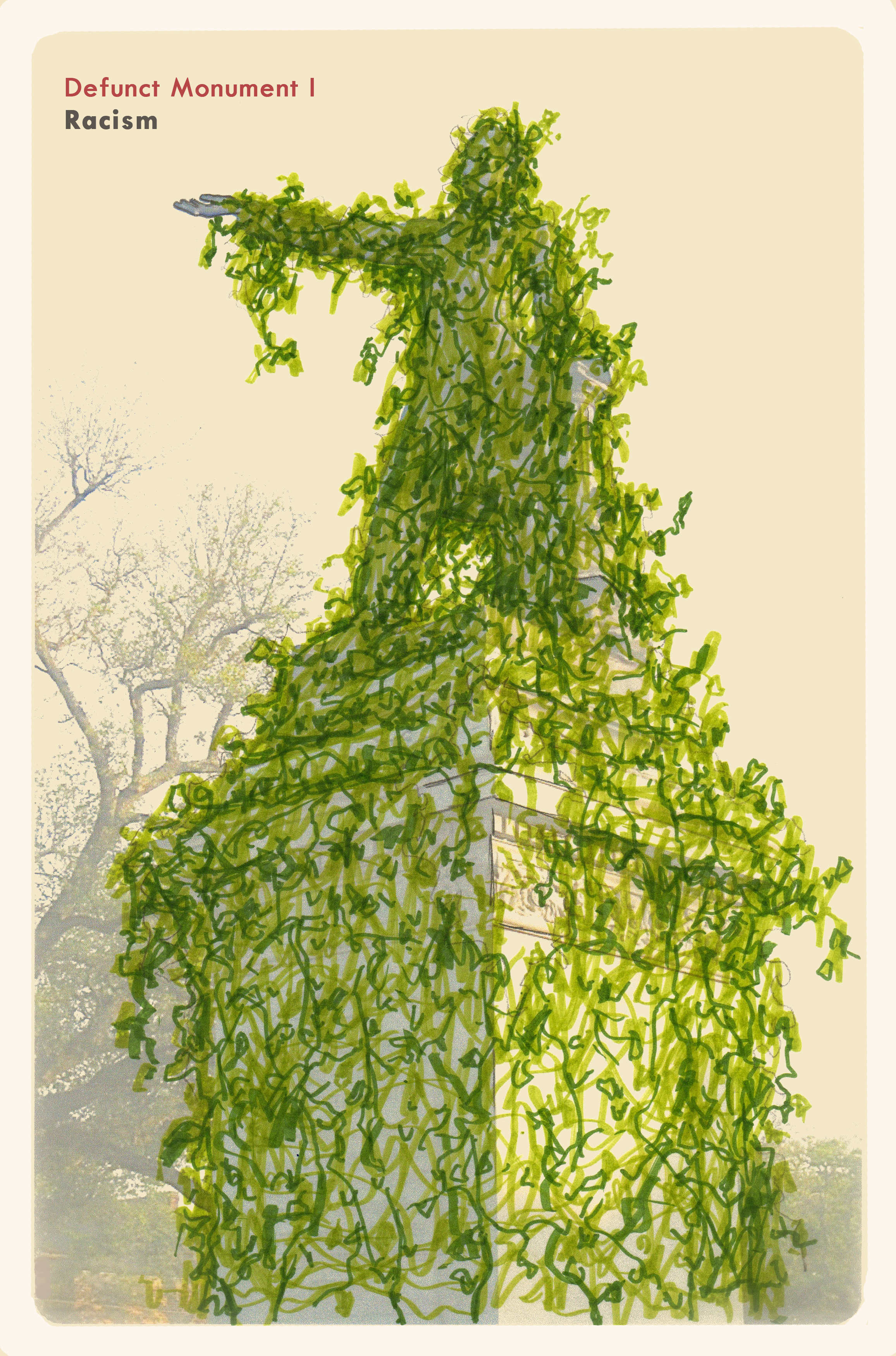

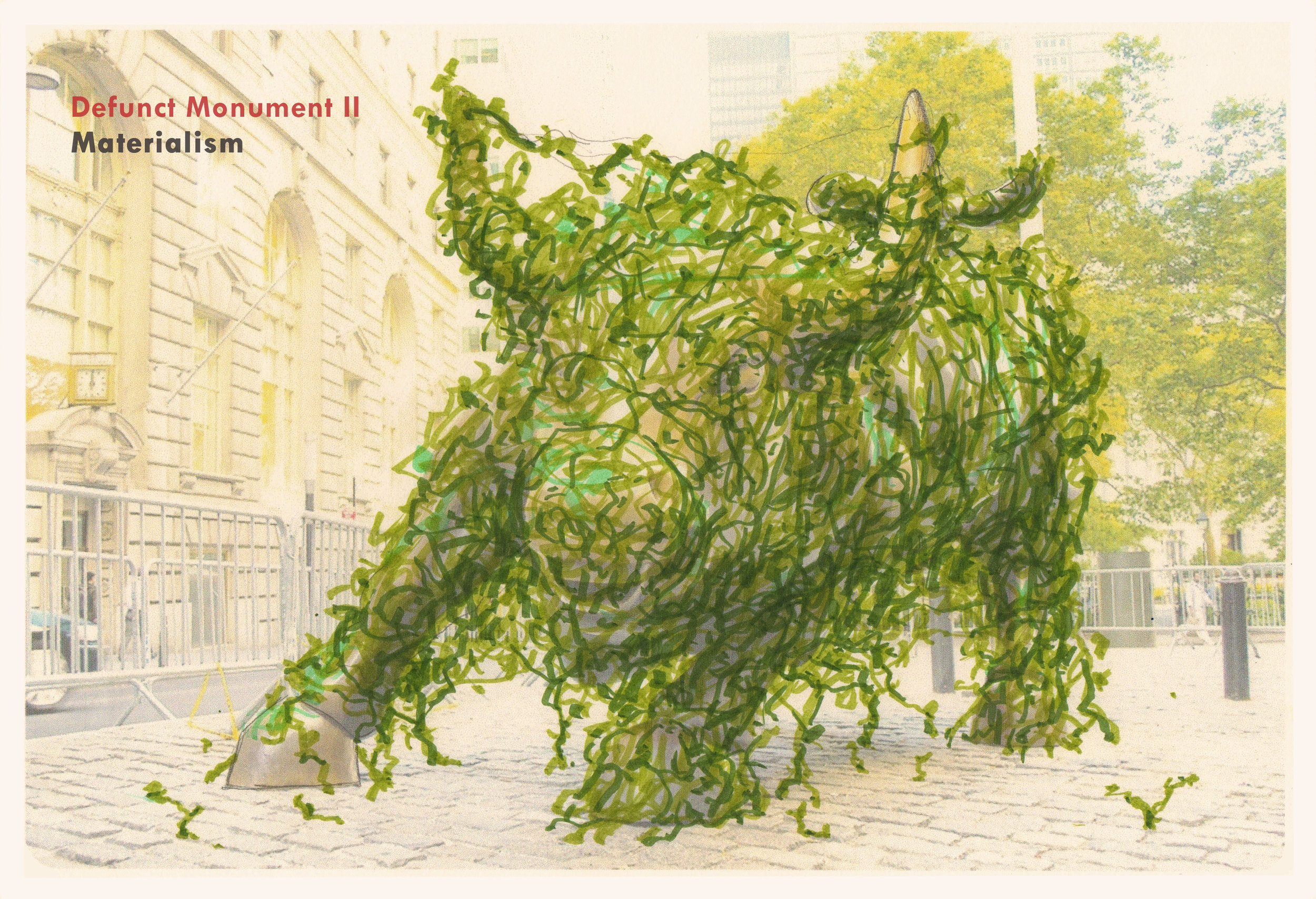

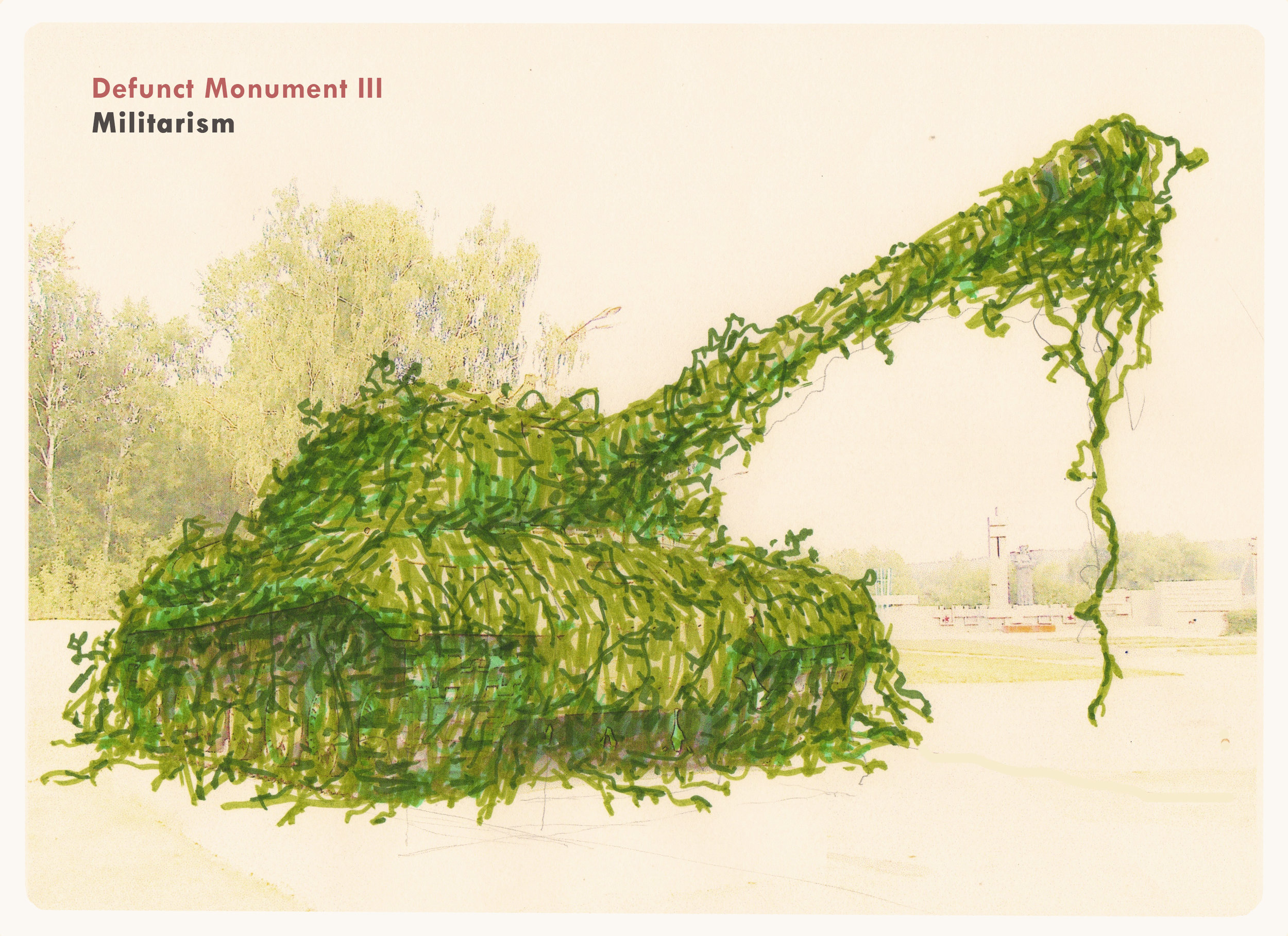

The triplets of racism, materialism and militarism

In support of the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture's national day of action #Revolution of Values, I made these 'postcards' of defunct monuments. They refer to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s April 4, 1967 Riverside Speech when he said,

[W]e as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a “thing-oriented” society to a “person-oriented” society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

They are influenced by my memory of kudzu consuming all sorts of man-made structures in Mississippi when I was working there in 2009. Soon after I made these, a group of artists from Charlottsville, VA, contacted me to ask if they could use “Defunct Monument I – Racism” as a model for an activist campaign they’d imagined. This led to the “Kudzu Project,” who’s members have been covering Confederate statues with hand-knitted kudzu as a way of symbolizing those monuments roots in a racist ideology.

Update: This statue was removed and put in storage on Wednesday, May 10th by the City of New Orleans.

Trashmore

(Originally published on my blog, “Blank Canvas” for Lawrence.com on March 10, 2006)

I've been waiting since January to write a little winter themed deal about where my friends and I used to go sledding as kids. But winter has fizzled out and my attention has turned towards planting seeds for the spring garden. This week I've been bringing trays of broccoli, lettuce, cauliflower, and kale starts outside to get a taste of what wind and squirrels are like, before transplanting them in early April. Maybe it's because I was raised in a place where gardening was next to impossible, but growing vegetables from seed to fruit still captivates me like a magician changing an egg into a live dove with a wave of his wand. In both cases, I have an idea of how the tricks are done, but I love them just the same.

I remember my mom trying to grow some beans outside our apartment window in Evanston, Illinois. They survived in the sun starved shadows and had just begun to develop skinny little inch-long fingers that I recognized as beans, when they were unceremoniously killed by the building super who had the all the apartment's window frames (and our bean plants) spray-painted battleship gray. As much as the blooming of the first daffodils around town lifts my spirits, I wish it had wintered more. I don't feel I've fully hibernated yet, and the bugs are bound to be hellacious due to the mildness. It's also been the first year, I can recall, that I haven't gone sledding even once.

When I was growing up in Evanston, we used to sled on a snow-covered hill of garbage called "Mt. Trashmore." The hill was owned by the city and was part of a big park where I played baseball in the summer. Rising on the horizon like a pregnant pimple, the 'mountain' was really just a bump with a staircase cut into it made out of railroad ties and one tow-rope for the kids who wanted to try out their new skis before they hit the big slopes in Wisconsin -- or if they were really lucky -- in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Although Trashmore was probably no more than 50 feet tall from its base to its rounded peak, it did have a nasty vertical drop that gave us kids a five second moment of glorious, out of control terror. The only drawback to the hill, as a winter resort, was that snow always seemed to melt twice as fast on its face compared to anywhere else. We couldn't figure it out back then, why all over town snow piled up in sub-zero weather, but Trashmore always turned to slush in a day or two.

Years later, a friend I grew up with told me that the pipes conspicuously poking out of the unused southern face, of our town's only mountain, were there to release warm gases from decades worth of disposable diapers, orange peels, used condoms, and other good stuff. On my last trip north to visit my dad in Evanston, I found the bedraggled old hill out of commission. 'No Trespassing' and 'Keep Out' signs littered the barren slopes, and there wasn't even a hint of snow. There were, however, people working in the community garden adjacent to the mountain. Incredibly, it looked like many gardeners had been able to grow a few greens and such through the winter. I don't know if all this muddy spring-winter weather is due to global warming or what, but the winters I recall along the Lake Michigan shore were full of ice floes, snow, and wind chills that froze spit before it hit the ground, and I miss them.